(This article first appeared in the online magazine www.kidmagwriters.com)

"I enjoyed your poem. You show great facility with iambic tetrameter."

My first response to the above quote from a Carus editor was, "Ah, shucks."

My second was... "Huh?"

I'm a Grandma Moses poet. Like that late-blooming primitive painter, I am self-taught. I once had an art teacher who stated that a true primitive painter is best left untaught. Too much information about composition and perspective, he said, might squelch a true primitive's natural flair. I'm probably the same way with my poetry writing. Or maybe I'm just too lazy to learn.

Either way, I write by the seat of my pants. I've never formally studied poetry except for a few moments in junior high and English 101 in college. Don't know a tetrameter from a tetrahedron; a spondee from a sponge cake. It's not that I haven't tried. I own a wonderful book, a 40-year-old high school textbook called LYRIC VERSE, edited by Edward Rakow. He keeps explaining spondees --and anapests and dactyls--- and I keep forgetting them. (Like the rules to cribbage, which my brother has explained to me at least 6 times.)

I compose mostly rhymed, metered poetry, which we all know is not held in high regard in certain academic circles. A poetry judge once told me that my work was better categorized as "light verse." Some might even call it doggerel.

Whaddevah. Kids don't care about labels. They just like solid, fun, rhythmic poetry.

Oops... I mean verse.

While I'm not heavily schooled in the NAMES of poetic forms, I have read a lot and learned by example. Often I'll encounter a poem, admire its particular rhythms, and borrow that beat to write a poem of my own.

In A TREASURY OF THE FAMILIAR, (Ralph L. Woods, MacMillan, 1943) a dusty old favorite inherited from my father, I came across "Burial of Sir John Moore" by Charles Wolfe. The poem begins this way:

Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

as his corse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O'er the grave where our hero we buried.

The poem continues in this plodding, dirge-like rhythm, which I found contagious. I was inspired to write a poem of my own, entitled "The Burial of Barnaby Briar." Here are the first three stanzas:

It was merciless midnight on All Hallows Eve,

In the murk of the mud and the mire,

that we hammered the lid on the coffin that hid

the body of Barnaby Briar.

And the rain never slacked on our suffering backs

as his coffin we grudgingly carried.

Not a star was in sight on that horrible night

that Barnaby Briar was buried.

All ‘round were the sounds of the creatures of night,

like the tune of a funeral choir,

while dark in our pockets the gold nuggets clanked

that we’d stolen from Barnaby Briar.

I think I've caught the tone of the earlier poem, thanks to that borrowed meter.

One talent is handy to a pants-seat poet: innate rhythm. When I was a kid, I thought I was just weird. I always wanted to clap along to music on the opposite beat from the -- let's admit it -- mostly white people around me. Anybody remember those circus TV shows in the 60s hosted by Don Ameche? Once, I asked my piano teacher what was wrong with me. Why did I always want to clap on the beat BETWEEN the claps of those European circus audiences?

"Because you've got rhythm," he said.

Then he explained the importance of the 2nd and 4th beat BETWEEN the plodding 1st and 3rd beats of a 4/4 song. You can hear clearly in rock songs. There's the drummer, hammering out that 2nd & 4th beat, between the stronger downbeats. (At least, I THINK the 1st & 3rd beats are called the downbeats. See? I told you I was unschooled.)

When I'm not stealing the rhythms of poets long dead, I enjoy writing within the constraints of specific poetic forms such as sonnets or limericks. Just another type of borrowing, I guess. For me, it's easier to grasp a form by studying an actual poem than by reading the spelled-out rules.

Read a few sonnets by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and you begin to naturally fall into that 10 syllable iambic beat:

AcCUSEme NOT, beSEECH thee, THAT i WEAR

Too CALM and SAD a FACE in FRONT of THINE;

As a lark, I knocked out the following sonnet on a dare. The assignment, from one of my critique group members, was to write a sonnet comparing poems to essays. Thus:

Shall I compare an Essay to a Verse?

by Kim Norman

A poem can be short and to the point,

while essays often drag on endlessly.

And essays often teachers disappoint,

but poems merely kill them by degree.

A poem may have rhythm, rhyme or meter,

while essays are most often writ in prose.

Although a poem's lyrics may be sweeter,

an essay often causes sweet repose.

A poem holds surprises like a prism,

obscuring deep emotions in a veil,

while essayists are prone to plagiarism

and other crimes that lead you straight to jail.

So I will pen a poem now and then

instead of writing essays from the "Pen."

I'll admit I broke a few rules. Because of female end-rhymes (rhymes that end in an unstressed syllable) a few lines in the above sonnet have eleven rather than the requisite ten syllables. It does conform to the 14 line, A-B-A-B rules, (3 quatrains & an ending couplet.) Since nobody reads this stuff, who's going to complain?

Do a few internet searches and you'll find a wealth of information about poetic forms. They're a great way to stretch your lyrical ligaments. Find something you like, read it a few times, then try one for yourself.

Happy borrowing!

###

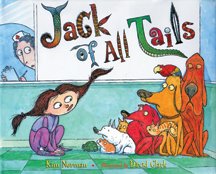

Kim Norman is the author of JACK OF ALL TAILS, (Dutton, 2007)

CROCODADDY, (Sterling, May 2009)

I KNOW A WEE PIGGY, (Dutton, 2010)

and TEN ON THE SLED, (Sterling, 2010

She writes (and borrows) in southeastern Virginia.

www.kimnorman.com

6 comments:

Kim, I write poetry, both rhymed and unrhymed and am a fairly new writer of children's stories. I think your suggestion to use another poem as a model is a good one, but in my experience those who don't have a good ear for meter have a hard time with this.

I play the flute and the piccolo and studied music for many years, and I'm convinced that is a big piece of why I have a good ear for meter.

I also generate most of my own rhymes (I have an altorithm) and rarely resort to a rhyming dictionary. I do make heavy use of a thesaurus -- I use the one at

http://www.dictionary.com

Thanks for an interesting article.

I think you're right that an innate sense of rhythm makes it a LOT easier to write marketable verse. (It's also true that studying music helps -- although the best musicians probably come to it with a lot of innate ability, too.)

I used to use a thesaurus more than I do now. I found that -- because I love words so much -- the vocabulary level of the piece would get too high for children's writing. So now I rely more frequently on simple rhymes I can compose in my own head... with the occasional trip to rhymezone.com

Good luck with your writing!

Kim

I love your sense of humor, Kim, both in your post and about Barnaby Brier. I plan to try some of your great suggestions right away. Thanks!

You're welcome, Donna. Glad you found it inspirational!

Kim

Kim that was a great article. I was totally able to relate. I grew up reading A A Milne's 'When we were very young and now we are six' have never had a poetry lesson in my life but still seem to be able to write publishable rhyming poetry so thanks for sharing. I don't feel like such a fraud now!

Oh yes, Milne! I have all his volumes of children's poetry and cherish them. I got a little choked up, when I sold my first book, to realize I was being published by the American publisher of Pooh. My absolute favorite when I was a kid. My mom threatened to throw the book away, she got so sick of reading it to me!

Post a Comment